By Kaitlin Wright

(Characters from 1967-77 Green Hornet TV Series featuring an Asian American sidekick)

Ask anyone, and they can rattle off a list of common “personas” found over and over again in movies. We know of the Prince Charming, the superhero, the bad guy, the evil stepmother, the princess, the damsel in distress, the sidekick, the henchmen, the comic relief etc. Each of these characters also seems to have a specific “image” or “look” that goes a long with them– Our superheroes are tall and muscular and our princesses are petite and delicate. These image stipulations are qualities that are agreed upon and accepted. When they are combated, sometimes they are ill-received for lack of alignment with the ideal image defined by society.

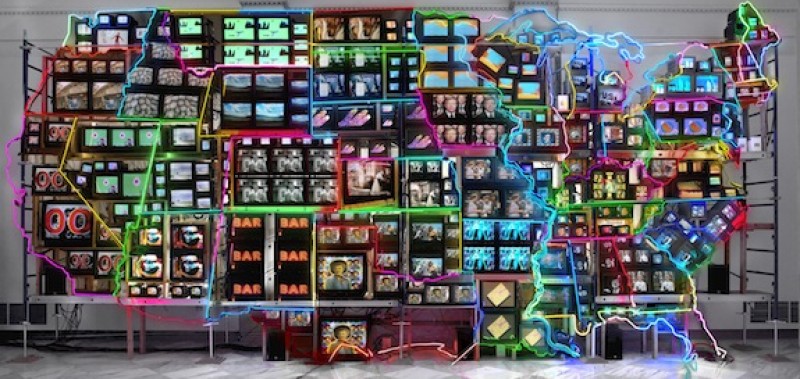

Celine Parrenas Shimizu in Straitjacket Sexualities writes, “we cannot idealize something without at the same time identifying with it” (202). This presents a problem for people of color who are often not cast in the “ideal” roles. Specifically thinking about the Asian American male and the roles he plays, we see that the characters’ qualities are used to highlight the primary, white lead. If the story is about a burly male figure, an Asian American role might be the foil that reveals “just how masculine the lead is” by accentuating the contrast between the Asian and the white physical/personality attributes. There is an artist named Deborah Lao who presented a series that featured five Asian American figures, that she said “represented the ideals behind the people, more than the people themselves” (Blum). With her art, Lao hopes to make the point that just because the Asian American male is often portrayed as the bumbling, nerdy guy who never gets the girl, doesn’t mean that all Asian American me fall into this one category. The images display Asian men from American culture that counter Asian anti-masculine stereotypes.

(Deborah Lao’s “Manhood” series)

The stereotypical images that the media presents are mere caricatures of people who lack something. This incomplete “other” is almost defined as a half-human. This incorrect representation leads to conflicts. For instance, a Native American child might want to grow up and be like John Wayne instead of the “bad” Indians represented in the movies, and Asian children would rather be like the powerful, Green Hornet hero as opposed to his sidekick. There is a defined mold in cinema and media in general that castrates the races from identifying completely with the primary characters. For people of color, this misidentification could breed a sense of inferiority, or shame in one’s heritage.

Shame is a topic that Shimizu brings up in Straitjacket Sexualites. She discusses the way that some Asian American male characters are shamed by the goofy roles they are asked to play. The Asian character, Long Duk Dong from the movie Sixteen Candles for example “deploys laughter in the face of his abjection” (118). This idea of shame is also discussed in terms of Asian American male sexuality. The homosexual Asian image is another point of contention for viewers, and it, like the “dorky Asian” image, shows how a fiction character can sometimes transfer to a real people. People begin to attribute certain qualities to the race as a whole, instead of accepting that the actor is being asked to portray a specific character.

Article on Deborah Lao’s “Manhood” Series: www.tigerstartups.com/blogs/433/deborah-laos-manhood-series-portraying-asian-american-masculinity